About / P. Adams Sitney + Florence Jacobs

The past week (June 10) has been gut-wrenching, with the passing of both Florence (“Flo”) Jacobs and P. Adams Sitney, two figures whose importance within the world of American experimental cinema can’t be overstated, and who occupied a place at the very heart of the NYC film community from the 1950s to the present day.

Though Flo never sought credit or publicity, and consistently ceded the limelight to her husband Ken Jacobs, she was his partner in his creative work as well as his life, and played an utterly indispensable role in the creation of many of his films and performances (as Amy Taubin has written, “Flo Jacobs is nothing less than the producer of Ken Jacobs’ cinema”, as well as “the most trusted other pair of eyes for his work, bringing to this task an aesthetic that is highly compatible with his own, but – and this is important – which was formed before she met him”). Ken & Flo’s body of work – one of the very greatest in the history of experimental cinema – wouldn’t have been the same without her. A wonderful painter in her own right, she was also among the kindest and most selfless of individuals. Every important creative community or movement is held together as much by its self-effacing, unifying figures as it is by its more assertive, celebrated personalities, and while Flo’s importance to the experimental film community of the past 75 years may be difficult to document, she was every bit as important as the filmmakers and artists whose work generates retrospectives and academic studies. She was beloved by generations of filmmakers, scholars, students, and cineastes, and the community won’t be the same without her.

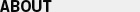

P. Adams Sitney was a foundational figure in the most literal sense – with his passing, Anthology has lost one of the last living links to its formation, and the world of American experimental film studies has lost arguably its foundational scholar. Alongside Jonas Mekas (as well as Peter Kubelka, Jerome Hill, and Stan Brakhage), P. Adams co-founded Anthology in 1966 (it would ultimately open in 1970). In 1974, after creating and editing the journal Filmwise as a teenager, writing extensively for Film Culture, editing Brakhage’s Metaphors on Vision, and editing several other volumes for Anthology, he published his seminal book Visionary Film. One of the very first – and certainly the finest and most comprehensive – historical/critical overviews of American avant-garde cinema, Visionary Film has remained the definitive text on the subject for the past 50 years. Without a doubt the preeminent historian of American experimental film, P. Adams also wrote brilliantly about European narrative cinema, as well as literature and poetry. He was a student of the literary giant Harold Bloom, taught generations of students at Princeton, and until the very end gave public talks at Anthology and other venues, which, thanks to his incredible erudition, charisma, and mischievous personality, were legendary. He has been a presiding spirit for the past 55 years here at Anthology, and his influence, example, and body of work are embedded in every part of what we do.

Anthology Film Archives, June 10, 2025

The following tribute to P. Adams was written by his Princeton colleague, Daniel Heller-Roazen:

The fact that the Princeton professor most intensely committed to introducing students to the ancient legacies of European and American literature, to Homer and Tacitus, Aeschylus and Dante, should have been the world’s foremost scholar of avant-garde film can be explained solely with respect to the unique path in life and writing that P. Adams Sitney cleared for himself. He began his undergraduate years at Yale as a student of Sanskrit, devoting himself to Classics and Comparative Literature. For him, as for his friend Guy Davenport, after Pound and Olson, the engagement with the archaic was to remain inseparable from a commitment to the most radical forms of expression in film and poetry.

P. Adams and I met in 2001 in a seminar at Princeton taught by Giorgio Agamben, who was then visiting. Agamben taught the first six weeks of the course; I did my best to continue on my own after he left. Students and auditors came from across the university and from other institutions to hear Agamben. P. Adams, whose astonishingly broad intellectual interests included contemporary European philosophy, attended the seminar as a faculty member, according to the almost unheard-of habit that he developed of sitting in regularly on courses taught by his colleagues. When Agamben returned to Italy and I took over the seminar, all the non-registered participants stopped attending, as was to be expected. P. Adams was the exception. We became friends.

In the next years, I came to learn that being the exception was the rule for P. Adams. At Princeton, he was the only professor appointed to teach the history of cinema. Despite the fact that he was a scholar of towering international stature, having published his first, much-discussed book, Visionary Film in 1974, before obtaining a PhD, despite the fact that his writing had been translated into many European and Asian languages, he was the only scholar at Princeton who had chosen to belong to a department for practising artists and creative writers, the Program in Visual Arts. He felt out of place, as he would often say, among “professional academics.” He had a unique drive to introduce the Humanities to undergraduates. For years, I co-taught freshman courses with him on ancient and medieval literature, art, religion, and philosophy. Alongside our students, I learned from P. Adams about Aristophanes, Ovid, classical and medieval painting, sculpture, architecture, theology, and the Bible. P. Adams discussed all those subjects with erudition, yet also with absolute humility, his lectures intermittently punctuated by unforgettable comedic insights. In those years, when he was raising his two younger daughters single-handedly with the utmost devotion, he seemed – almost magically – at once infinitely available for students and always present for friends.

P. Adams was tireless in teaching the history of film and the theory and poetics of filmmakers. Because of his commitment to showing students cinema in the medium in which it was conceived, he saw to it that Princeton became a place where, each week, anyone could discover or see again extraordinary films by Dreyer, Brakhage, Straub-Huillet, Deren, Markopoulos, Bresson, Warhol, Hou Hsiao-hsien, Menken, Tarkovsky, Frampton. (I was such a lucky “anyone.”) P. Adams also regularly invited artists and filmmakers to the University to show and discuss their films, welcoming Peter Kubelka, Yvonne Rainer, Robert Beavers, Morgan Fisher, Nathaniel Dorsky, and Ernie Gehr. P. Adams thereby offered students, professors, and people in the area the chance to learn about those artists’ work and the vital commitments that sustained them.

For P. Adams was sensitive, as no scholar I have known, to the existential challenges that a creative life puts to the maker. From the years when he began collecting films as a teenager and Jonas Mekas entrusted him with the task of introducing European audiences to the work of the New American Cinema, he developed an almost religious respect for the ethics of the artist. Hence his lifelong commitment to supporting films and writing that, without him, might never have been seen or read – from his crucial early effort to make Blanchot’s prose available in English to the founding role he played at Anthology Film Archives, to his uninterrupted dedication to filmmakers whom he knew for decades or whom he met later in life, who have yet to receive the attention that they deserve. Hence, too, the extreme generosity and encouragement that he never ceased to show younger and older poets, writers, and scholars. P. Adams was a critic for whom criticism consists not in discussing what there is to see and to read, as is often assumed today, but in judging, as the root of the word “criticism” suggests: in calling our attention to what, without the critic’s intuition, might well escape our notice – and in cultivating the sensitivity to what is most remarkable, most provocative, and most nourishing in it.

The ancient historian Polybius once remarked that “it can happen that by ignorance and lack of judgment, many people are not, so to speak, where they are, and they do not see what they see.” With an energy and enthusiasm that only death could extinguish, P. Adams never stopped pointing us to the unknown places where we are, showing us what we have yet to see.

Daniel Heller-Roazen

June 12, 2025